When my great-grandfather was alive in the 1900s, roughly 10% of the world’s population lived in cities. The 50% mark was passed in 2007 – not that long ago. By 2050, around 75% of the world’s population will be living in some form of city or urban agglomeration. This is due to two things: the first is natural birth – more people in cities are giving birth to more children, and they’re living healthier lives. The second is national and international migration. Of course, migration is what cities have been about for thousands of years, attracting people because of jobs, opportunities and education.

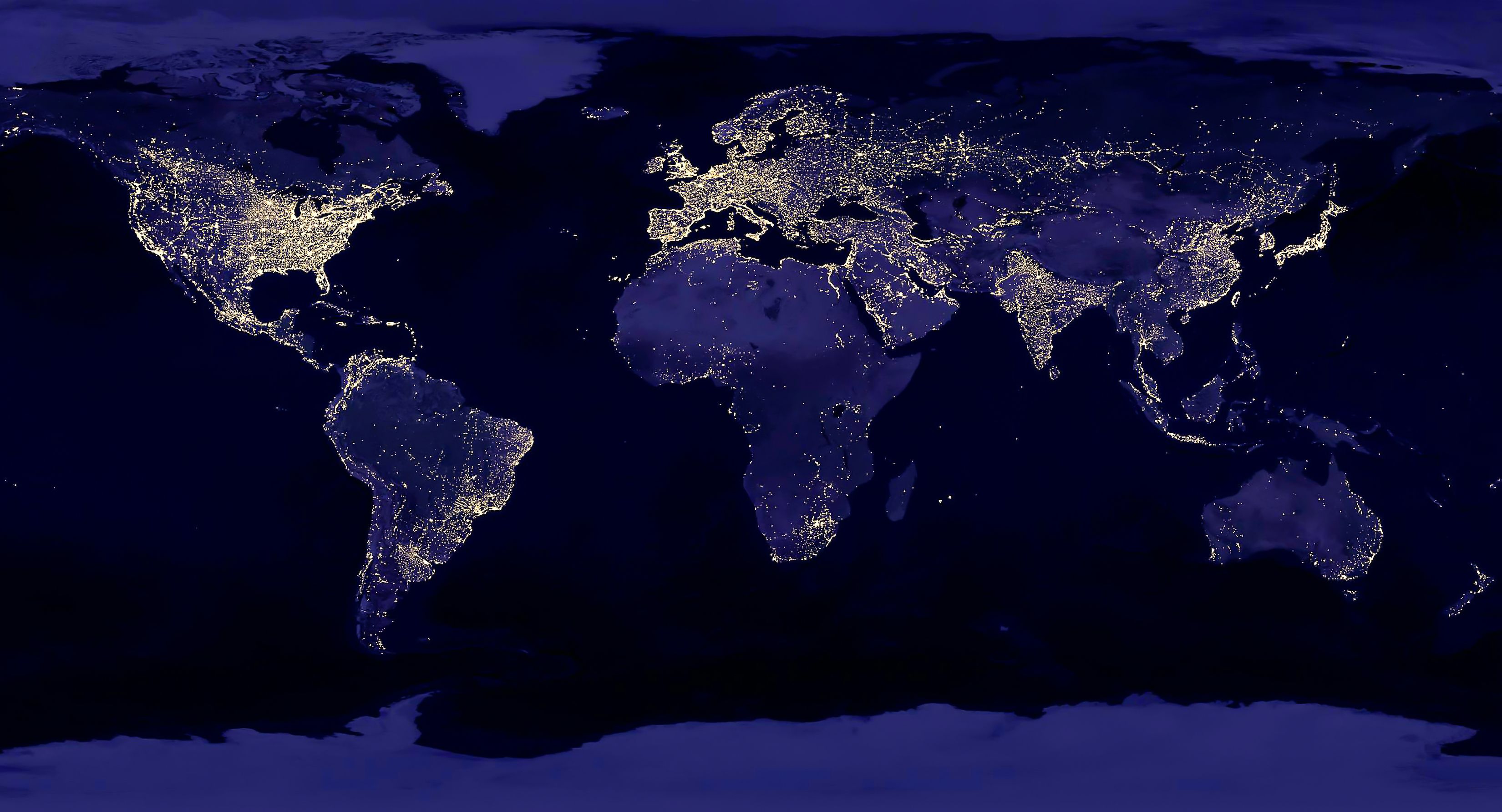

As we reflect on urban growth and changing patterns around the world, we need to think about issues of scale, speed and geographical distribution. Most of the urban growth in the next 30 years will happen in parts of Asia and Africa, where the economy is not as advanced as in other parts of the world, but it’s growing and picking up speed very quickly. The economy of some of the countries in East Asia and South East Asia – China, Singapore, Malaysia or India – are, instead, strong and increasingly urbanised.