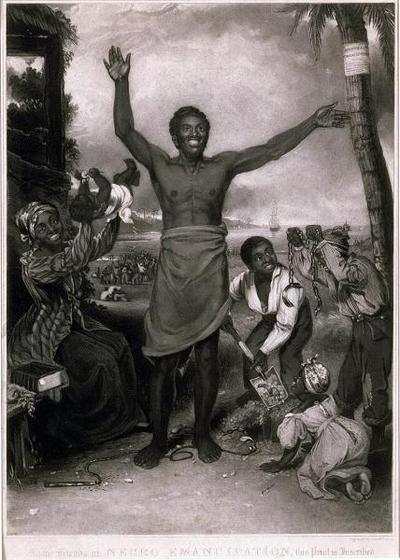

Some of the earliest contributors to this writing were freed slaves who wrote autobiographies and were living in London. One in particular, Olaudah Equiano, wrote an autobiography, which was published in 1789. This book went into at least 15 different editions and several European translations. He was one of the first writers to inscribe not only the experiences of the transatlantic slave trade, but also the experience of being in London, which he saw as a form of refuge from the world that he had come from.

There were many others at the time. Another writer, Ignatius Sancho, lived in Greenwich and had a long correspondence with Laurence Sterne. Sancho, interestingly, talked about his relationship to Britain as being ‘that of a lodger and only that’ – a trope that Hanif Kureishi picks up in the 20th century when he opens his famous novel The Buddha of Suburbia with ‘My name is Karim Amir, and I am an Englishman born and bred, almost.’ This sense of being adjacent to English culture, being adjacent to Britain, runs right through from the 18th century to the present day.