There's a metaphor that people often use when they're trying to explain Kant's philosophy. People say it was Kant's view that each of us carry around innate spectacles through which we view the world. So when we're looking at the world and when we're trying to find out what the world's like, we ourselves are making a contribution to what we're presented with because we ourselves are supplying these spectacles through which we view things. That's very significant for Kant because, apart from anything else, it meant that by reflecting on the nature of these spectacles we could anticipate how the world was going to appear to us. But “appear” is the operative term. If you imagined that you were always looking at the world through literally rose-tinted spectacles everything would appear to have a rosy hue. Similarly, they ensure that the world appears to us a certain way. But that has no implications for how the world in itself really is.

Adrian Moore

Kant's philosophy and the spectacles through which we see the world

Adrian Moore, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Oxford, discusses Kant’s view of the transcendent and the great metaphysical questions.Key Points

- • Kant believed in a transcendent realm beyond how we see things through our ‘spectacles.’

- • Kant believed that the great metaphysical questions relating to the existence of God and an afterlife could never be answered, but that didn’t make them less vital.

- • By acknowledging that there was no answer, Kant left the door open for the development of faith.

Our “innate spectacles”

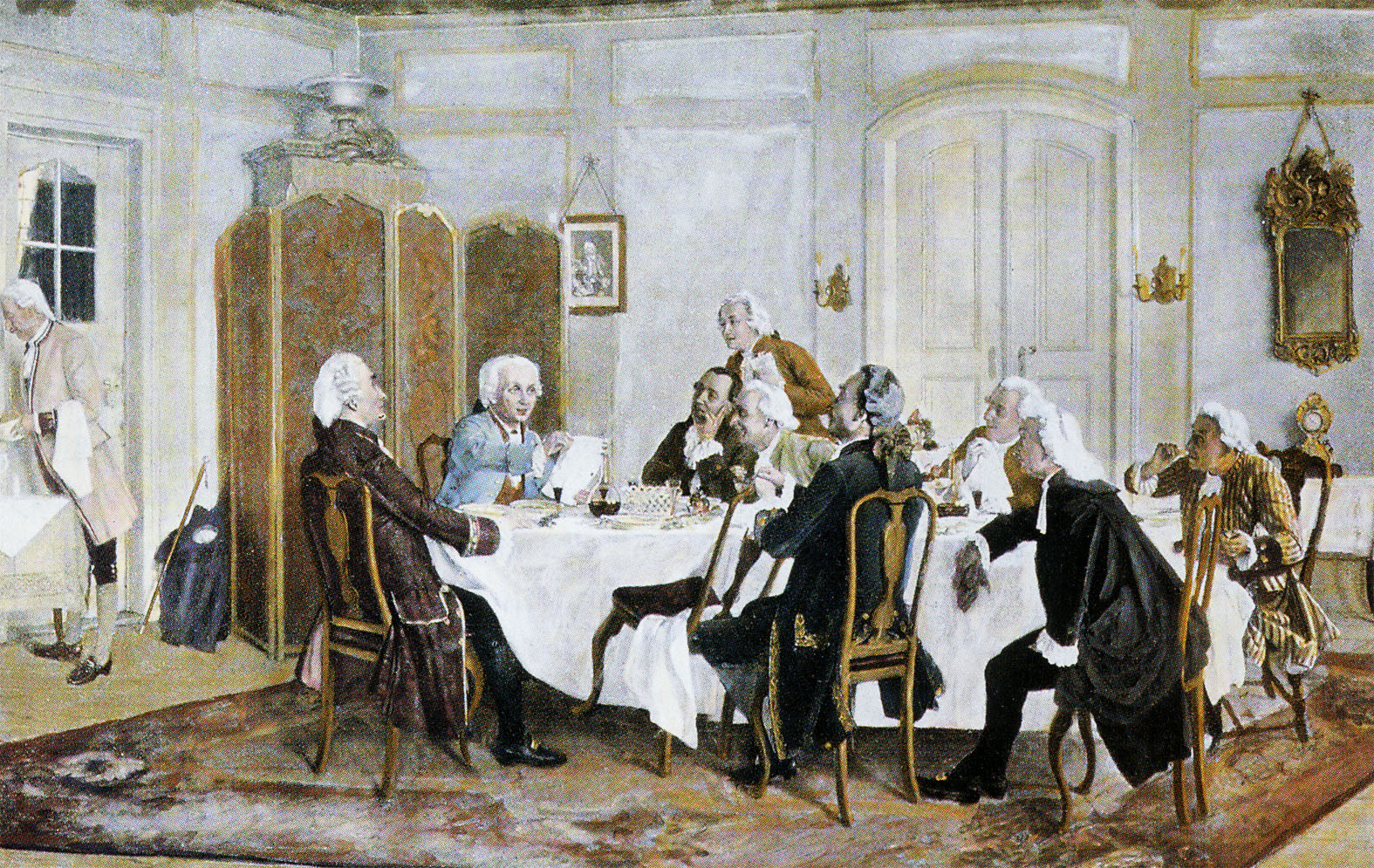

Kant and friends at table painting 1882/1893. Photo by Emil Doerstling. Wikimedia commons. Public Domain.

The transcendent realm of how things are in themselves

The one thing that Kant was adamant we couldn't do was take them off. We couldn't take our spectacles off to look at reality directly to see how the world was in itself. What this meant, and the reason why all of this is relevant to the question of the transcendent, is that for Kant there was always something transcendent to be reckoned with. There was always the question, ‘How are things in themselves? What's the real nature of that reality out there?’ We can see how it appears to us; we can say a lot about how it appears to us; we can anticipate a lot about how it will appear to us. We can't know how it is in itself; we can't look beyond our spectacles; we can’t gain insight into this transcendent realm. But for Kant, there certainly is such a thing as a transcendent realm because if there's such a thing as appearance then there must be such a thing as the reality with which it has to be contrasted.

The great metaphysical questions

So there's Kant working with this very fundamental distinction between how things appear, and how they transcendently are in themselves. And that's a distinction that his own philosophical system has committed to. But here's the twist: if we think about the great questions of metaphysics that philosophers have wrestled with for centuries, many of them were questions that Kant would have recognised as being in the transcendent realm. In particular, this was true of the most urgent and most compelling great metaphysical questions, and the ones that really mattered to us. He did think that metaphysical questions mattered to all of us, and not just to philosophers.

Photo by FrameAngel

In particular, there were three great questions that he always singled out. First is whether there's a God or not, and who isn't exercised by that question? Secondly, whether human beings enjoy some sort of immortality, or some sort of afterlife or existence beyond the here and now. The third great question was whether we have free will. For Kant, all three of these questions were about the transcendent realm and all three of them were questions that we could not hope to answer. Kant's own system had precluded the possibility of answering these great questions of metaphysics. He was telling us the most that we could ever do was speculate on their answers. We couldn't use any of the resources that we had to our disposal to settle any of these three questions.

Finding meaning in these questions

Somebody might say, ‘The only things we can really understand, the only things that make sense to us, are the things that we can experience. And there you are, Kant, telling us that that means things that we can see through our spectacles and beyond that it’s not just mere speculation. It’s worse than that. It’s nonsense; it’s meaninglessness.’ In many ways, that was the kind of reaction that Kant’s great predecessor Hume had. He would certainly have been ready to dismiss questions about what transcends our experience as meaningless questions. That wasn't Kant’s attitude at all. It was actually a significant part of Kant’s system that things appeared to us a certain way, in contrast to how they really were in themselves. But this meant that there was such a thing as how things really were in themselves, and speculation about how things really were in themselves was genuine speculation. This was not sheer gibberish. These questions were not meaningless questions. The fact that we couldn't answer them didn't mean that they failed to make sense. So the great metaphysical questions that people had been wrestling with in the past were, in Kant’s view, perfectly genuine questions. The problem was that we didn't have any hope of answering them.

Leaving room for faith

Photo by DangBen

In a way, this is a good news story as well as a bad news story, because what it meant was that significant room had been left for faith and, in particular, for faith in God's existence, in our own freedom and in the possibility that there was some sort of existence over and above the here and now, where perhaps some of the injustices of the here and now might eventually be rectified. Kant's most important philosophical work was the Critique of Pure Reason and in the second edition of that book he wrote a preface in which he said the following: ‘I had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith.’

Kant believed that all of these great metaphysical questions which we had no way of answering were nevertheless of supreme importance to us. It was also of supreme importance to us that we could have faith, that certain answers to these questions held and that we could direct our lives according to that faith, because it was Kant’s belief that everything that really mattered, everything that was really valuable, everything that was really important in our lives was tied up with this transcendent realm of how things were in themselves. And in particular they were tied up with our own freedom, our own ability to direct our lives of our own free will, in relation to the existence of a God and in relation to the possibility of some kind of existence beyond the here and now where there was room for hope, as well as faith, that some of the injustices of this life could ultimately be rectified.

Discover more about

Kant and the transcendent realm

Wood, A. W. (1978). Kant's Rational Theology. Cornell University Press.

Moore, A.W. (2003). Third Theme: Religion, Third set of variations. In Noble in Reason, Infinite in Faculty: Themes and Variations in Kan'ts Loral and Religious Philosophy (pp. 147–196). Routledge.

Moore, A.W. (1988). Aspects of the Infinite in Kant. Mind, New Series, 97(386), 205–223.

About Adrian Moore

Here's how we use cookies

To give you the best experience, we tailor our site to show the most relevant content and bring helpful offers to you.

You can update your preferences at any time, at the bottom of any page. Learn more about how your data is used in our cookie policy.