He also talks about writing it in darkness, referring to his own blindness. It’s difficult to think what it must have been like to write this as a blind man. So, he has this sense of himself as a kind of prophetic figure, a figure who’s been singled out in some way and given their destiny. He imagines himself as having what he calls in the poem ‘fit audience, though few’, so, even then, he was reconciling himself with the fact that Paradise Lost was likely to have a small readership. It’s interesting that Milton himself acknowledged that fact.

Joe Moshenska

Why we should read John Milton's poetry today

Joe Moshenska, Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford, talks about John Milton’s poetry.Key Points

- • What distinguishes John Milton is that he was very acutely attuned to the larger tensions in the society around him. He had a powerful sense of his own individuality but also of the importance of thinking collectively.

- • Milton’s most famous work was Paradise Lost, his epic poem on the fall of humankind in the Garden of Eden.

- • In Paradise Lost, Milton reimagines Bible passages: he takes a story that’s full of gaps, suggestions and possibilities and fills it with the power of his own imagination.

Why read Milton today?

The reason to read John Milton’s poetry today is that he captures the most exciting, extreme conflicts and tensions of his own time and can therefore resonate with the conflicts and tensions of ours. They’re not the same, but by seeing how he wrestles with the predicaments in which he found himself, the opportunities that he identified, we can take a great deal for the ways in which we meet our own challenges and opportunities.

Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

The individual and the collective

What distinguishes John Milton is that he was very acutely attuned to the larger tensions in the society around him – and very conflicted about them. One of the things that’s exciting about his poetry is that you can read it as the working out of those conflicts. In the 17th century, the status of the individual was very much disputed in new ways: the extent to which the individual had a right to, for example, protect his or her rights against the desires of monarchs to exert their power – the proper role of the individual in society in relation to the larger whole or collective.

What’s extraordinary about Milton, in that regard, is that he had this incredibly powerful sense of his own individuality – his own specialness, his destiny to do great things, his sense of himself as marked out, in some way; however, he also had a countervailing set of convictions about the importance of thinking collectively and of making sense, not just of himself, but of the broader nation and the whole of the human race of which he was a part.

Paradise Lost

Milton’s most famous work, and the work in which he wrestled the most with the question of what it meant to make – and to be the kind of person capable of making – a great poem, was Paradise Lost, his epic poem on the fall of humankind in the Garden of Eden.

In Paradise Lost, there is a mixture of impulses, or ways of understanding himself, that fed into his acts of poetic creation. You have this sense of Milton, the historical individual who is trying to make sense of his predicament at the time that he wrote the poem. He wrote it around the time of the restoration of the monarchy of Charles II, when Milton had to go into hiding as one of the figures who had defended the regicide of Charles I very publicly.

Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

A heroic creator?

The account he gives, in the poem, of the way it came to him is very different from the sense of a heroic individual forging these materials into a shape all by himself and through his own powers of imagination and his own efforts. He seems to have believed – and to want the reader to believe – that he was being visited each night by a divine muse, so he would wake with the next portion of the poem ready-made in his head. His role was to dictate it to one of his scribes, his amanuensis, possibly one of his daughters, who would do the writing for him. He would then fix and edit it.

So, there’s an incredibly mixed sense of him being, on the one hand, this figure who is a heroic creator in his own right, and on the other hand, the much more archaic sense of the poet as a conduit for something, as someone who allows inspiration to flow through him.

The sentences of Paradise Lost are labyrinthine – extremely long and complicated. He writes in paragraphs of verse instead of couplets or shorter units, and that really conveys the sense of someone who feels like the poem is happening to him and, in some sense, also wants it to happen to us, as we read it.

Reimagining passages from the Bible

The extraordinary thing about the opening of the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible is how incredibly meagre it is. There’s very little in that story. It’s short, vague and full of interesting suggestions, hints and implications. Actually, these days, we tend to encounter rewritten Bible stories, rather than the thing itself. It’s amazing how much isn’t there. For example, there’s no indication that the serpent is actually Satan, or the devil.

Milton’s taking this very brief story that’s full of gaps, suggestions and possibilities, and he’s filling it with the power of his own imagination. In the process, he’s taking us into places – the minds of devils, the outer reaches of the cosmos, the Garden of Eden itself – and asking very surprisingly direct questions. We find ourselves, in the course of the poem, dwelling with questions like, ‘Do angels eat?’; ‘Do they have sex?’; ‘What would it be like to receive God’s commands as an angel?’; ‘What would it be like to discover yourself, for the first time, as a fully conscious individual?’; ‘What are those first moments of consciousness like?’ So, he starts with something quite brief and suggestive and turns it into something filled with these imaginative possibilities and speculations.

Milton’s views of women

I think it’s fair to say that Milton’s views of women and his implications as a writer for women is one of the most complicated and difficult aspects of him to come to terms with. You can certainly find, throughout his writings, very straightforward and unequivocal statements of misogyny, of a hierarchical understanding of the relationship between the sexes.

In Paradise Lost, when he introduces Adam and Eve, he’s straightforward. He says ‘he for God only, she for God in him’. Adam has the direct relationship with the divinity and Eve’s is entirely mediated through her husband. All that said, I do think there are ways in which Paradise Lost gives us more than simply an Eve who is subordinated to her husband. Perhaps the most interesting moment of the poem in that respect is the point at which she first awakens, having been created, and she goes to a pool of water, sees herself reflected in it and is captivated by her own reflection. What’s very interesting is that when she sees Adam for the first time, she finds him less pleasing than the reflection of herself in the pool that she saw and has to be guided back to him.

As with so much in Milton, you can read this in two ways: you can see it as simply reinforcing a sense of the first woman as vain and self-regarding. There is another way of reading it, however, which is that you’re being shown the origins of a social structure coming about – you’re being shown that heterosexuality and women’s subordination are not natural.

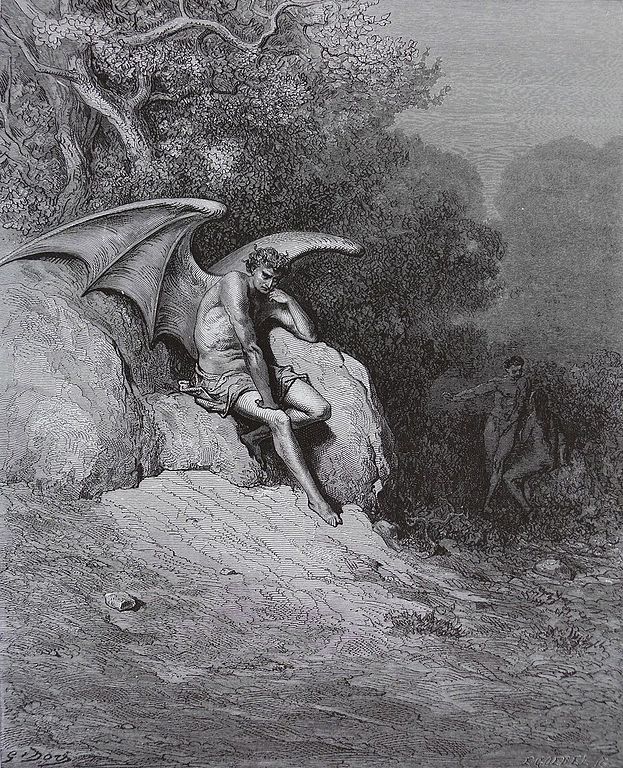

Satan’s role in Paradise Lost

Many readers of Paradise Lost have found Satan to be its most compelling figure. Even if you’re not always sympathising with him, he is a magnetic centre to the text – this tragic, overreaching figure who has refused to remain in his position of divinely decided subordination and strives for something more. Also, the fact that we are in such physical proximity to Satan is something that sometimes gets left out of that sense of him being heroic. There’s an extraordinary passage in Book Two of the poem, where Satan has to go across a realm called Chaos in order to get to Earth and is bombarded by these natural forces and thrown around. He wriggles and squirms his way across this realm where up, down, left and right don’t mean anything anymore. It’s an incredible moment of disorientation. We’re with him in the thick of these things. We spend a lot of time in that kind of closeness to Satan before we see Adam and Eve, before we meet God or any of the other unfallen angels. William Blake most famously said that ‘Milton was of the devil’s party, though he knew it not’, because of this unwitting sympathy on Milton’s part towards Satan.

Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

John Milton and Thomas Hobbes

The interesting thing about the pairing of Milton and Hobbes is that the greatest closeness between them is not directly connected to their politics. They both had a very strong view of the world as a material set of forces; they both insist upon the materiality of the spirit and the idea of, as Milton calls it in Paradise Lost, ‘one first matter all’ – this idea that matter issues from God and is given dignity by God. They take that in very different directions: for Hobbes, the material world is a disenchanted war of conflicting forces without a divine umpire, whereas for Milton, it’s rather a matter being imbued with divine potential and capable of being perfected and transformed in different ways.

What makes it exciting to me is that how you understand the fundamental makeup of the world or of creation, as Milton thinks of it, is not separate from your politics or your religion. These spring from this underlying view of how all things work. So, there’s a considerable degree of similarity underlying massively opposed views of the political world.

A crucial document for human rights

In the 40s, when Milton was very active as a writer of prose tracts, he wrote a tract titled “Areopagitica”, which was addressed to parliament and called for an end to pre-publication censorship of writing. Milton argued very powerfully in that text that ideas need to be allowed into society. They need to be encountered, even – or, perhaps, especially – when they are wrong. This tract has become a key point of reference for subsequent debates about free speech and censorship. It was translated into French and adapted in the midst of the French Revolution. It was read avidly by the American Founding Fathers – and there is a possibility that it had an influence on the Declaration of Independence and the way that it was written. So, it finds its way into many of these subsequent debates. It is also the most rhetorically powerful and extraordinary piece of prose that Milton ever wrote.

Discover more about

John Milton

Moshenska, J. (Forthcoming, 2021). Making Darkness Light: A Life of John Milton. Basic Books.

Lewalski, B. (1999). The Life of John Milton: A Critical Biography. Wiley-Blackwell.

Smith, N. (2008). Is Milton Better than Shakespeare? Harvard University Press.

About Joe Moshenska

Here's how we use cookies

To give you the best experience, we tailor our site to show the most relevant content and bring helpful offers to you.

You can update your preferences at any time, at the bottom of any page. Learn more about how your data is used in our cookie policy.